|

Amasa Delano Notes |

CHAPTER V.

I have now arrived at a point in my narrative, where it is more proper for me, than at any other place, to introduce a subject, which has excited much interest in the public mind, and which is calculated to afford many valuable reflections upon human character. This subject is the singular family which has been discovered on Pitcairn's Island, and which sprung from the mutineers of the English ship Bounty, and the Otaheitan women whom they carried with them. The reasons which I have for interweaving this story with my narrative, will I trust be thought sufficient. At Timor, I found in the possession of governor Vanjon, a manuscript history of the cruise of the Pandora, written by Captain Edwards himself, who was sent out by the English government, in search of the Bounty and the mutineers. This manuscript I copied, and shall present the substance of it to the reader. I have also lived a considerable time with Captain Folger, the first person who visited, the family upon Pitcairn's Island, and from whom most of the information concerning the state of it has been derived. He very often conversed with me upon this subject, and gave me a number of details which have not been before printed. These details cannot be communicated to the public in a proper form without introducing an abstract of the whole history. It has been considered advisable therefore to devote this chapter to an account of Bligh's expedition and its consequences. I have been at the expense of having a plate cut from Carteret's voyage, to give to my readers a map of Pitcairn's Island, and thus to furnish the |

best idea or it which the present state of our knowledge will admit. The most interesting facts, recorded in other books, will be found in this chapter, and to these some additions will be made from the information which it has been in my power to obtain. It is well known, that Lieutenant William Bligh was selected by the English goverment [sic] in 1787, to command an expedition to Otaheite to obtain the bread-fruit tree for the West Indies. His commission was dated the 16th of August. The vessel, purchased and fitted out for this object, was named the Bounty, with a reference to the nature of the enterprise. A very convenient arrangement was made in it for a garden of pots with the bread fruit plants. The crew consisted of forty six persons, of whom twenty one were officers, twenty three were seamen, and two were gardeners. The Bounty sailed from Spithead on Sunday the 23d of December, 1787. She attempted first to make her passage by the way of Cape Horn, and was in sight of Terra del Fuego March 11th, 1788. But in consequence of the difficulty of the navigation in this course, Lieutenant Bligh determined, with advice, to go by the way of the Cape of Good Hope, and changed his direction accordingly the 22d of April. He stayed thirty eight days in False Bay, and sailed again the 1st of July. Passing the island of St. Paul, Mewstone near the south west cape of Van Dieman's Land, and Adventure Bay, where he anchored the 20th of August, he discovered, the l9th of September, a cluster of small rocky islands, in latitude 47° 41' south, and in longitude 179°,7' east, thirteen in number, and a hundred and forty five leagues east of the Traps, which are near to the south end of New Zealand. These he named after the ship, the Bounty Isles. The 25th of October, he saw the island Maitea, called Osnaburg by Captain Wallis the discoverer, and at six in the evening he saw Otaheite. He anchored in Matavai Bay the 26th, and a great number of canoes came immediately around him. The natives inquired if the people in the ship were tyos, friends, and if they were from Pretanie, Britain, or from Lima. As soon as they were satisfied, they crowded the decks of the Bounty, without regarding the efforts which were made to prevent them. Lieutenant Bligh stayed at Otaheite twenty three weeks. During this time, he and his crew became intimately acquainted with the na- |

tives, and were treated with the greatest hospitality. They inter-changed civilities in the ship and on shore, and lived in the exercise of mutual good will. Many very interesting details are to be found in the history of this period. No appearances of discontent, on the part of the crews were discovered. At one time indeed three seamen deserted, but they surrendered themselves afterwards, and were received. The 6th of February, 1789, all the bread-fruit plants, amounting to 1015, were taken on board in a healthy state. Besides these, the Bounty had a number of other plants, "the avee, one of the finest flavoured fruits in the world; the ayyah, not so rich, but of a fine flavour and very refreshing; the rattah, not much unlike a chesnut; the orai-ah, a superior kind of plantain; the ettow and matte, with which the natives make a beautiful red colour; and a root called peeah, of which they make an excellent pudding." The 4th of April, Lieut. Bligh stood out to sea from Toahroah harbour, and on the 23d he anchored at Annamooka, one of the Friendly islands. This place he left the 26th, and on the 27th was between the islands of Tofoa and Kotoo, in latitude 19° 18' south. He steered westward to go south of Tofoa, and gave orders for this direction to be followed during the night. The master had the first watch, the gunner the middle watch, and Mr. Christian the morning watch. Thus far the voyage had been peaceful and prosperous. After this the scene changed. The following is the account given of the mutiny by Lieutenant Bligh himself. "Tuesday, the 28th, just before sun rising, while I was yet asleep, Mr. Christian, with the master at arms, gunner's mate, and Thomas Burkitt, seaman, came into my cabin, did seizing me, tied my hands with a cord behind my back, threatening me with instant death, if I spoke or made the least noise. I however called as load as I could in hopes of assistance; but they had already secured the officers, who were not of their party, by placing sentinels at their doors. There were three men at my cabin door, besides the four within. Christian had only a cutlass in his hand; the others had muskets and bayonets. I was hauled out of bed, and forced on deck in my shirt, suffering great pain from the tightness with which they had tied my hands. I demanded the reason of such violence, but received no other answer, than abuse for not holding my tongue. The master, the gunner, the surgeon, Mr. |

Elphinston, master's mate, and Nelson, were kept confined below; and the fore hatchway was guarded by sentinels. The boatswain and carpenter, and also the clerk, Mr. Samuel, were allowed to come upon deck, where they saw me standing abaft the mizen-mast with my hands tied behind my back, under a guard, with Christian at their head. The boatswain was ordered to hoist the launch out, with a threat, if he did not do it instantly, to take care of himself. "When the boat was out, Mr. Haywood and Mr. Hallet, two of the midshipmen, and Mr. Samuel, were ordered into it. I demanded what their intention was in giving this order, and endeavoured to persuade the people near me not to persist in such acts of violence; but it was to no effect. 'Hold your tongue, Sir, or you are dead this instant,' was constantly repeated to me.. "The master by this time had sent to request that he might come on deck, which was permitted; but he was soon ordered back again to his cabin. "I continued my endeavours to turn the tide of affairs, when Christian changed the cutlass, which he had is his hand, for a bayonet that was brought to him, and holding me with a strong gripe by the cord that tied my hands, he with many oaths threatened to kill me immediately, if I would not be quiet. The villains round me had their pieces cocked and bayonets fixed. Particular people were called on to go into the boat, and were hurried over the side; whence I concluded that with these people I was to be set adrift. I therefore made another effort to bring about a change, but with no other effect than to be threatened with having my brains blown, out. "The boatswain and seamen, who were to go in the boat, were allowed to collect twine, canvass, lines, sails, cordage, an eight and twenty gallon cask of water, and Mr. Samuel got a hundred and fifty pounds of bread, with a small quantity of rum and wine, also a quadrant and compass; but he was forbidden on pain of death to touch either map, ephemeris, book of astronomical observations, sextant, time keeper, or any of my surveys or drawings. "The mutineers having forced those of the seamen, whom they meant to get rid of, into the boat, Christian directed a dram to be served to each of his own crew. I then unhappily saw that nothing could be done to effect the recovery of the ship. There was no |

one to assist me, and every endeavour on my part was answered with threats of death. "The officers were next called upon deck, and forced over the side into the boat, whilst I was kept apart from any one, abaft the mizen-mast, Christian, armed with a bayonet, holding me by the bandage that secured my hands. The guard round me had their pieces cocked, but on my daring the ungrateful wretches to fire, they uncocked them. "Isaac Martin, one of the guard over me, I saw, had an inclination to assist me, and as he fed me with shaddock, my lips being quite parched, we explained our wishes to each other by our looks; but this being observed, Martin was removed from me. He then attempted to leave the ship, for which purpose he got into the boat; but with many threats they obliged him to return. "The armourer, Joseph Coleman, and two of the carpenters, McIntosh and Norman, were also kept contrary to their inclination; and they begged of me, after I was astern in the boat, to remember that they declared they had no hand in the transaction. Michael Byrne, I am told, likewise wanted to leave the ship. "It is of no moment for me to recount my endeavours to bring back the offenders to a sense of their duty. All I could do was by speaking to them in general, but it was to no purpose, for I was kept securely bound, and no one except the guard suffered to come near me. "To Mr. Samuel I am indebted for securing my journals and commission, with some material ship papers. Without these I had nothing to certify what I had done, and my honour and character might have been suspected, without my possessing a proper document to have defended them. All this he did with great resolution, though guarded and strictly watched. He attempted to save the time keeper, and a box with my surveys, drawings and remarks for fifteen years past, which were numerous, when he was hurried away with 'Damn your eyes, you are well off to get what you have.' "It appeared to me that Christian was sometime in doubt whether he should keep the carpenter, or his mates: at length he determined on the latter, and the carpenter was ordered into the boat. He was permitted, but not without some opposition, to take his tool chest. "Much altercation took place among the mutinous crew during the whole business. Some swore,'I'll be damned if he does not find |

his way home, if he gets any thing with him,' meaning me: And when the carpenter's chest was carrying away, 'Damn my eyes, he will have a vessel built in a month' While others laughed at the helpless situation of the boat, being very deep, and so little room for those who were in her. As for Christian, he seemed as if meditating destruction on himself and every one else. "I asked for arms, but they laughed at me, and said I was well acquainted with the people among whom I was going, I therefore did not want them. Four cutlasses however were thrown into the boat, after we were veered astern. "The officers and men being in the boat, they only waited for me, of which the master at arms informed Christian; who then said, 'Come, captain Bligh, your officers and men are now in the boat, and you must go with them. If you attempt to make the least resistance, you will instantly be put to death:' and without further ceremony, with a tribe of armed ruffians about me, I was forced over the side, where they untied my hands. Being in the boat, we were veered astern by a rope. A few pieces of pork were thrown to us, and some clothes, also the cutlasses I have already mentioned; and it was then that the armourer and carpenters called out to me to remember that they had no hand in the transaction. After having undergone a great deal of ridicule, and been kept some time to make sport for these unfeeling wretches, we were at length cast adrift in the open ocean. "I had with me in the boat the following persons:

|

"In all twenty-five hands, and the most able seamen of the ship's company. "Having little or no wind, we rowed pretty fast towards Tofoa, which bore north east about ten leagues from us. While the ship was in sight, she steered to the west north west, but I considered | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

this only as a feint; for when we were sent away, "Huzza for Otaheite" was frequently heard among the mutineers. "Christian, the chief of the mutineers, is of a respectable family in the north of England. This was the third voyage he had made with me; and as I found it necessary to keep my ship's company at three watches, I had given him an order to take charge of the third, his abilities being thoroughly equal to the task; and by this means the master and gunner were not at watch and watch. "Haywood is also of a respectable family in the north of England, and a young man of abilities, as well as Christian. These two had been objects of my particular regard and attention, and I had taken great pains to instruct them, having entertained hopes that as professional men they would have become a credit to their country. "It will very naturally be asked, what could be the reason for such a revolt; in answer to which I can only conjecture, that the mutineers had flattered themselves with the hopes of a more happy life among the Otaheitans than they could possibly enjoy in England; and this joined to some female connexions most probably occasioned the whole transaction. "The women at Otaheite are handsome, mild and cheerful in their manners and conversation, possessed of great sensibility, and have sufficient delicacy to make them admired and beloved. The chiefs were so much attached to our people, that they rather encouraged their stay among them than otherwise, and even made them promises of large possessions. Under these, and many other attendant circumstances, equally desirable, it is now perhaps not so much to be wondered at, though scarcely possible to have been foreseen, that a set of sailors, most of them void of connexions, should be led away; especially when in addition to such strong inducements they imagined it in their power to fix themselves in the midst of plenty, on one of the finest islands in the world, where they need not labour, and where the allurements of dissipation are beyond any thing that can be conceived." Such is the account, which Lieut. Bligh has given of this mutiny. The boat, into which so many persons were forced, was twenty three feet long, six feet and nine inches wide, and two feet nine inches deep. In this they passed many islands, ran along the coast of New Holland, and on the 14th of June, a period of forty seven days from the mutiny, landed at Timor. Their sufferings and dan- |

gers were extreme. "The abilities of a painter perhaps could seldom have been displayed to more advantage than in the delineation of the two groupes of figures which at this time presented themselves to each other. An indifferent spectator would have been at a loss which most to admire, the eyes of famine sparkling at immediate relief, or the horror of their preservers at the sight of so many spectres, whose ghastly countenances, if the cause had been unknown, would rather have excited terror than pity. Our bodies were nothing but skin and bones, our limbs were full of sores, and we were clothed in rags. In this condition, with the tears of joy and gratitude flowing down our cheeks, the people of Timor beheld us with a mixture of horror, surprise, and pity. The governor, Mr. William Adrian Van Este, notwithstanding extreme ill health, became so anxious about us, that I saw him before the appointed time. He received me with great affection, and gave me the fullest proofs that he was possessed of every feeling of a humane and good man." From Timor Lieut. Bligh went to Batavia, and from thence he sailed to England, where he arrived and landed at Portsmouth, the 14th of March, 1790. Out of the nineteen, who were forced into the launch, twelve survived the hardships of the voyage, and revisited their native country. The 7th of November the same year, Capt. Edward Edwards. sailed from England in the ship Pandora, to search for the Bounty and the mutineers. He went round Cape Horn to Otaheite, where he arrived the 23d March, 1791, having touched at Tenerife and Rio Janeiro. The substance of his account is as follows. After we entered Matavia bay, Joseph Coleman, one of the mutineers, and several natives came on board. In the course of the day, Peter Haywood, George Stewart, and Richard Skinner, also of the Bounty's crew, came on board. From them we learned that the Bounty had been twice at Otaheite, since she had been in possession of the pirates; that she sailed from thence on the night of the 21st of September, 1790, with Fletcher Christian, Edward Young, Matthew Quintal, William McKoy, Alexander Smith, John Williams, Isaac Martin, William Brown, John Mills, and several male and female natives of the island; that Joseph Coleman, George Stewart, Peter Haywood, Thomas Burkitt, John Sumner, James Morrison, John Millward, Henry Hilbrant, Charles Norman, Thomas McIntosh, |

Michael Byrne, William Musprat, Thomas Ellison, Richard Skinner, Charles Churchill, and Matthew Thompson, were left at Otaheite by their own desire; and that some of them had sailed from Matavia bay, on the very morning before our arrival, for Papara, a distant part of the island, where some other of the pirates lived. They went in a schooner, which they had built for themselves. In consequence of this intelligence, we sent two boats in pursuit of them the same evening, but the pirates saw the boats, and put to sea immediately in their schooner. The boats chased her, but the wind blowing fresh, she outsailed them, and they returned to the ship. The schooner had, as it was said, very little water or provisions on board, and could not continue long at sea. Persons were employed to look out for her, and give information, should she return to the island. The 25th of March, Michael Byrne came on board the Pandora, and delivered himself up, In the morning of the 27th, intelligence was received that the schooner had returned to Papara, and the pirates were gone into the mountains to conceal and defend themselves. Mr. Corner, the second lieutenant, was sent in a few hours in the launch with twenty six men to take them; and Mr. Hayward, the third lieutenant, was sent in the pinnace with a party to join the launch. In the evening of the 28th the launch brought to the ship James Morrison, Charles Norman, and Thomas Ellison, three of the pirates taken at Papara. The schooner was captured the 1st of April. On the 7th, Corner and Hayward marched with a party round the island on the opposite side from Papara, and succeeded in taking all the pirates. They had left the mountains, and were near the shore when they were discovered. They surrendered themselvea on being commanded to lay down their arms. It was reported to us, that Charles Churchill had been killed by Matthew Thompson, several months previous to our arrival, and that Thompson was afterwards killed by the natives, and offered as a sacrifice for the murder of Churchill, whom they had made a chief. We learned that Christian, after he had turned Lieutenant Bligh adrift, went with the Bounty to the island Toobouai, and intended to settle there. But being in want of many things necessary for this purpose, he returned to Otaheite to procure them. He told the natives that Lieutenant Bligh was left at an island, which he had discovered, and where he designed to make a settlement. The |

ship had come to Otaheite to get hogs, goats, bread fruit trees, other plants, and various seeds. The natives believed the story, and gave a supply of every thing which they had. Christian then returned to Toobouai, taking with him several women. He and his companions had nearly finished a fort at this place, when they agreed to abandon it, because of quarrels among themselves, and wars with the natives, which they had brought on by their depredations. They determined by a majority of votes, to go to Otaheite, and there leave as many as desired it. Accordingly the sixteen men, already mentioned, were left, while the others went away with the ship. Most of their spare masts, yards, and booms, were lost at Toobouai. The small arms, powder, canvass, and stores were divided equally among them all. The only intelligence which we could obtain after this period, was, that the Bounty was seen to the north west on the morning after she sailed; that Christain[sic] had been heard frequently to say that he would seek an uninhabited island in which there was no harbour for ships; and that he would run the Bounty ashore, break her up, and get from her whatever would be useful to him in his intended settlement. Provided as he was with live stock, plants and seeds, and having women with his men, this plan was highly probable. The pirate schooner was equipped as a tender; two petty officers and seven men were put on board of her; and we left Otaheite the 8th of May. We visited most of the islands in the neighborhood, and proceeded to Whylootacke and Palmerston. On the latter we found a yard marked Bounty's driver yard. We could not however, by any examination, discover the track of the Bounty or her people. In searching for information around this island, we lost a midshipman and four seamen in a cutter. The yard was supposed to have drifted hither from Toobouai. Hilbrant, one of our prisoners, told us, that Christian had declared to him, he would go to an island near to Danger Island, which answered the description of the Duke of York's, discovered by Byron, and if he found it suited to his purpose, he would stay there. In consequence of this, we visited that island, and some others in the neighborhood, but found no traces of the ship or the mutineers. |

The 23d of June, we lost sight of the tender, off the island Oahtooah, and never saw her again. After cruising two days about this place, we made the best of our way to Rotterdam, one of the Friendly Islands. We had agreed in case of separation to rendezvous there. We visited Navigator's Islands, passed Pylsaarts, examined Middleburgh and Amsterdam, saw several not delineated in any chart, and returned to Rotterdam. We sailed thence the 2d of August, with the intention to go to England by Endeavour Straits. On the 25th, we fell in with a reef, and with islands which we supposed were connected with it, on the east side of New South Wales. Along this reef we sailed south inclining to the east, searching for an opening in it, which we found on the morning of the 26th. We sent an officer in a boat to examine the opening, and were informed by signal that it had water enough to permit the ship to run through. It lies in latitude 11°, 12' south, and longitude 216° 22' west. Signal was made for the boat to come on board, but it was night before she reached us, and we lost sight of her. By discharging guns and burning fires we made known our situations to each other. About half past seven in the evening, we got soundings in fifty fathoms water. At the same moment, the boat was seen close to our stern. We thought the water was discoloured, and hauled our tacks on board; but before the sails could be trimmed, and just as the boat got along side, the ship struck upon the reef. We hoisted out the boats to carry off an anchor, but before this object could be accomplished, the ship made so much water that it became necessary to employ every body at the pumps and in bailing. We had more than eight feet of water in the hold. Soon after this, the ship beat over the reef. We let go an anchor, and brought her up in fifteen fathoms. The water gained upon us only in a small degree, and we flattered ourselves for some time, that by the assistance of a thrummed topsail, which we were preparing, and intended to haul under the ship's, bottom, we should be able to free her from water. This flattering hope did not continue long. As she settled in the water the leak increased so fast, that there was reason to apprehend she would sink before daylight. But with great exertion at the pumps and in bailing, we put off this event till we saw the sun rise, and had an opportunity to ascertain our situation and its danger. We kept our boats astern, and put into them a small quantity of provisions and |

other necessary articles. We made rafts, and unlashed the booms and every thing else upon deck. At half past six, the hold was full; water was between decks; it washed in at the upper deck ports; we began to leap overboard, and take to the boats; but all could not get out of her before she actually sunk. The boats continued astern, in the direction of the tide from the ship, and picked up the people who had laid hold of rafts and other floating articles which had been cast loose for this purpose. We loaded two of the boats with people, end sent them to an island about four miles distant. Boats were immediately dispatched again to look about the wreck and the reef for those who were missing, but returned without finding an individual. Being mustered, we found that eighty nine of the ships' company, and ten of the pirates who were prisoners on board, were saved; and that thirty one of the ship's company, with four of the pirates, were lost. We hauled up the boats to fit them for our intended run to Timor; we took an account of provisions and other articles saved; and spread them out to dry. We put ourselves on the following allowance: three ounces of bread, which was occasionally reduced to two; half an ounce of portable soup; half an ounce of essence of malt; one glass of wine; and two glasses of water, The soup and malt were not issued till after we left the island. In the afternoon of the 30th, we sent a boat to the wreck to see if any thing could be procured. She returned with the head of a top gallant mast, a little of the top gallant rigging, and part of the lightning chain, but without a single article of provision. A boat was sent to fish, but returned with the loss of a grapnel, and without a fish. The boats were completed and launched the 31st; we put every thing we had saved on board; and at half after ten in the forenoon we embarked. The island, or key, that we left, was only thirty two yards across at high water, and a little more than double the distance in length. It produced not a tree, nor a shrub, nor a blade of grass. It had no water, and the only useful article, which we procured there, was a few shell fish. We steered north west by west. We soon discovered that the water in two of our largest vessels was so bad as to be rejected even by people in our situation, and that we had not twenty gallons fit to be drank. We saw land the 1st of September, probably |

New South Wales, and sent the yawl ashore. Water was found, and two kegs were filled. We ran into a bay of what Lieutenant Bligh calls Mountainous Island, and there saw Indians on the beach. They waded off to us, we made them small presents, and gave them to understand that we wanted water. They filled a vessel for us, and returned to fill it again. They made signs for us to land, but we declined. Just as a native was stepping from the shore to bring us a second vessel of water, an arrow was shot at us, and stuck in the quarter of the boat. We fired a volley of muskets, and they fled. We had previously seen that they were collecting bows and arrows, and were upon our guard. We afterwards landed at what we named Plum Island, from a species of plum we found upon it; but we obtained there no water. We steered our course in the evening for the Prince of Wales Islands, and at 11 o'clock at night came to a grapnel in a sound near one of them. The next morning we landed, and by digging, found good water. We filled all our vessels, and two canvass bags besides, which we had made for this purpose. But with all this, we had only a gallon of water for each man. We sent our kettles on shore, made tea and portable soup, picked a few oysters off the rocks, and had the best meal we had made since the day before the wreck. The 2d of September, we saw the northern extremity of New South Wales, which forms the south side of Endeavor Straits. From this we took our departure and sailed westward. The allowance of bread, three ounces, the people could not eat, because of excessive heat and thirst. Indeed we suffered more from these two causes than from hunger. The 13th of September, at 7 o'clock in the morning, we saw Timor. Land was never beheld with greater pleasure. We gave him, who first discovered the island, two glasses of water, and to the others one. The yawl and the launch hauled in for the land, and we were soon separated from them. Thinking we saw the month of a river, we stood for it; a party swam ashore in search of water; but the supposed river was only the tide of the sea amid islets of mangrove trees. We saw fires on a beach to the south and west; two of our people swam ashore but saw no person, and found no water. We continued our run, and at half past six in the morning of the 14th, we heard a cock crow. We went on shore, found good water, bought some fish of a party of Indians, were joined by the launch, rowed out to clear a |

reef, and then stood to the west till we entered the straits of Semau in the afternoon of the 15th. On the morning of the 16th, according to our account, we hailed the fort at Coupang, and informed the people who we were. A boat was sent for us. Lieutenant Hayward and myself landed, and were received by Mr. Frey the Lieutenant Governor, and Mr. Bonberg, captain lieutenant of a Company's ship lying in the roads. They conducted us to Governor Vanjon, who received us with his characteristic humanity and courtesy. Refreshments were immediately prepared for us; the people ordered to land, and provisions supplied; and all dined at the Governor's own house. He gave orders for us afterwards to be received on board the Bamberg, a ship of the Dutch East India Company, commanded by W. Van Dadulbeek, to be carried to Batavia. Such is the substance of the account of Captain Edwards. That part of it, containing the transactions at Otaheite, is given in a brief way in the Quarterly Review for July 1815, in the article Porter's Cruise, where it is also added, that of the ten who were taken to England for trial before a court martial, six were condemned to suffer death, and four were acquitted. Those condemned were Haywood, Morrison, Ellison, Burkitt, Millward, and Muspratt. "To the two first of these his Majesty's royal mercy was extended at the earnest recommendation of the court, and the last was respited, and afterwards pardoned." Those acquitted were Norman, Coleman, McIntosh, and Byrne. After mentioning Christian's departure from Otaheite, as it has already been given in the account by Edwards, the Quarterly Review proceeds as follows: – "From this period, no information respecting Christian or his companions reached England for twenty years; when about the beginning of the year 1809, Sir Sidney Smith, then commander in chief on the Brazil station, transmitted to the Admiralty a paper which he had received from Lieutenant Fitzmaurice, purporting to be an extract from the log book of Captain Folger, of the American ship Topaz, and dated Valparaiso 10th of October, 1808. This we partly verified in our review of Dentrecasteaux's voyage, by ascertaining that the Bounty had on board a chronometer made by Kendal, and that there was on board her a man of the name of Alexander Smith, a native of London. |

"About the commencement of the present year, [1815] Rear Admiral Hotham, when cruising off New London, received a letter addressed to the Lords of the Admiralty, of which the following is a copy, together with the azimuth compass to which it refers. "March 1st, 1813.

"My Lords, "The remarkable circumstance which took place on my last voyage to the Pacific ocean, will, I trust, plead my apology for addressing your Lordships at this time. In February 1808, I touched at Pitcairn's Island, in latitude 25° 5' south, longitude 130° west from Greenwich. My principal object was to procure seal skins for the China market; and from the account given of the island in Capt. Carteret's voyage, I supposed it was uninhabited; but on approaching the shore in my boat, I was met by three young men in a double canoe, with a present consisting of some fruit and a hog. They spoke to me in the English language, and informed me that they were born on the island, and their father was an Englishman, who had sailed with Capt. Bligh. After discoursing with them a short time, I landed with them, and found an Englishman, of the name of Alexander Smith, who informed me he was one of the Bounty's crew, and that after putting Capt. Bligh in the boat, with half the ship's company, they returned to Otaheite, where part of the crew chose to tarry; but Mr. Christian, with eight others, including himself, preferred going to a more remote place, and after making a short stay at Otaheite, where they took wives, and six men servants, proceeded to Pitcairn's Island, where they destroyed the ship, after taking every thing out of her, which they thought would be useful to them. About six years after they landed at this place, their servants attacked and killed all the English, excepting the informant, and he was severely wounded. The same night the Otaheitan widows arose and murdered all their countrymen, leaving Smith with the widows and children, where he had resided ever since without being resisted. I remained but a short time on the island, and on leaving it Smith presented me with a time-piece, and an azimuth compass, which he told me belonged to the Bounty. The time-keeper was taken from me by the governor of the island of Juan Fernandez, after I had had it in my possession about six weeks. |

The compass I put in repair on board my ship, and made use of it on my homeward passage, since which a new card has been put to it by an instrument maker in Boston. I now forward it to your Lordships, thinking there will be a kind of satisfaction in receiving it merely from the extraordinary circumstance attending it. (Signed,) MAYHEW FOLGER.

"Nearly about the same time a further account of these interesting people was received from Vice Admiral Dixon, in a letter addressed to him by Sir Thomas Staines, of his Majesty's ship Briton, of which the following is a copy. ""Briton, Valparaiso, October 18th, 1814.

"SIR, "I have the honour to inform you, that on my passage from the Marquesas Islands to this port, on the morning of the 17th September, I fell in with an Island where none is laid down in the Admiralty or other charts, according to the several chronometers of the Briton and Tagus. "I therefore hove to until daylight, and then closed to ascertain whether it was inhabited, which I soon discovered it to be, and to my great astonishment, found that every individual on the island (forty in number) spoke very good English. They prove to be the descendants of the deluded crew of the Bounty, which from Otaheite, proceded to the above mentioned Island, where the ship was burnt. Christian appeared to have been the leader and sole cause of the mutiny in that ship. A venerable old man, named John Adams, [there is no such name in the Bounty's crew; he must have assumed it in lieu of his real name Alexander Smith,] is the only surviving Englishman of those who last quitted Otaheite in her, and whose exemplary conduct and fatherly care of the whole of the little colony, could not but command admiration. The pious manner in which all those born on the island have been reared, the correct sense of religion which has been instilled into their young minds by this old man, has given him the pre-eminence over the whole of them, to whom they look up as the father of the whole and one family. A son of Christian's was the first born on the island, now about twenty five years of age, (named Thursday |

October Christian;) the elder Christian fell a sacrifice to the jealousy of an Otaheitan man, within three or four years after their arrival on the island. They were accompanied thither by six Otaheitan men, and twelve women: the former were all swept away by desperate contentions between them and the Englishmen, and five of the latter have died at different periods, leaving at present only one man and seven women of the original settlers. The island must undoubtedly be that called Pitcairn's, although erroneously laid down in the charts. We had the meridian sun close to it, which gave us 25° 4' south latitude, and 130° 25' west longitude, by chronometers of the Briton and Tagus. It is abundant in yams, plantains, hogs, goats, and fowls, but affords no shelter for a ship or vessel of any description; neither could a ship water there without great difficulty. I cannot however refrain from offering my opinion that it is well worthy the attention of the laudable religions societies, particularly that for propagating the christian religion; the whole of the inhabitants speaking the Otaheitan tongue as well as English. During the whole of the time they have been on the island, only one ship has ever communicated with them, which took place about six years since, by an American ship called the Topaz, of Boston, Mayhew Folger master. The Island is completely iron bound, with rocky shores, and landing in boats at all times difficult, although safe to approach within a short distance in a ship. (Signed,) T. STAINES.

"We have been favoured with some further particulars on this singular society which we doubt not will interest our readers as much as they have ourselves. As the real position of the island was ascertained to be so far distant from that in which it is usually laid down in the charts, and as the captains of the Briton and Tagus seem to have still considered it as uninhabited, they were not a little surprised on approaching its shores, to behold plantations regularly laid out, and huts or houses more neatly constructed than those on the Marquesas Islands. "When about two miles from the shore, some natives were observed bringing down their canoes on their shoulders, dashing through a heavy surf, and paddling off to the ships; but their astonishment was unbounded, on hearing one of them on approach- |

ing the ship, call out in the English language, 'wont you heave us a rope now?' The first man who got on board the Briton soon proved who they were; his name he said was Thursday October Christian, the first born on the island. "He was then about five and twenty years of age, and is described as a fine young man about six feet high; his hair deep black; his countenance open and interesting, of a brownish cast, but free from that mixture of a reddish tint which prevails on the Pacific Islands; his only dress was a piece of cloth round his loins, and a straw hat ornamented with the black feathers of the domestic fowl. 'With a great share of good humour,' says Captain Pipon 'we were glad to trace in his benevolent countenance all the features of an honest English face.' 'I must confess,' he continues, 'I could not survey this interesting person without feelings of tenderness and compassion. His companion was named George Young, a fine youth of seventeen or eighteen years of age. If the astonishment of the captains was great on hearing their first salutation English, their surprise and interest were not a little increased on Sir Thomas Staines taking the youths below and setting before them something to eat, when one of them rose up, and placing his hands together in a posture of devotion, distinctly repeated, and in a pleasing tone and manner, 'for what we are going to receive, the Lord make is truly thankful.' They expressed great surprise on seing [sic] a cow on board the Briton, and were in doubt whether she was a great goat, or a horned sow. The two captains of his Majesty's ships accompanied these young men on shore. With some difficulty and a good wetting, and with the assistance of their conducters, they accomplished a landing through the surf; and were soon after met by John Adams, a man between fifty and sixty years of age, who conducted them to his house. His wife accompanied him, a very old lady blind with age. He was at first alarmed lest the visit was to apprehend him; but on being told that they were perfectly ignorant of his existence, he was relieved from his anxiety. Being once assured that this visit was of a peaceable nature, it is imposible to describe the joy these poor people manifested on seeing those whom they were pleased to consider as their countrymen. Yams, cocoanuts, and other fruits, with fine fresh eggs, were laid before them; and the old man would have killed and dressed a hog for his visitors, but time would not allow them to |

partake of his intended feast. This interesting new colony, it seemed now consisted of about forty six persons, mostly grown up young people besides a number of infants. "The young men all born on the Island were very athletic, and of the finest forms, their countenance open and pleasing, indicating much benevolence and goodness of heart; but the young women were objects of particular admiration, tall, robust, and beautifully formed, their faces beaming with smiles and unruffled good humour, but wearing a degree of modesty and bashfulness that would do honour to the most virtuous nation on earth; their teeth like ivory, were regular and beautiful, without a single exception; and all of them, both male and female, had the most marked English features. The clothing of the young females consisted of a piece of linen reaching from the waist to the knees, and generally a sort of mantle thrown over the shoulders, and hanging as low as the ancles; but this covering appeared to be intended chiefly as a protection against the sun and the weather, as it was frequently laid aside, and then the upper part of the body was entirely exposed, and it is not possible to conceive more beautiful forms than they exhibited. They sometimes wreath caps or bonnets for the head in the most tasty manner, to protect the face from the rays of the sun; and though as Captain Pipon observes, they have only had the instruction of their Otaheitan mothers, 'our dress makers in London would be delighted with the simplicity and yet elegant taste of these untaught females.' Their native modesty assisted by a proper sense of religion and morality instilled into their youthful minds by John Adams, has hitherto preserved these interesting people perfectly chaste and free from all kinds of debauchery. Adams assured the visitors that since Christian's death there had not been a single instance of any young woman proving unchaste, nor any attempt at seduction on the part of the men. They all labour while young in the cultivation of the ground, and when possessed of a sufficient quantity of cleared land and of stock to maintain a family, they are allowed to marry, but always with the consent of Adams, who unites them by a sort of marriage ceremony of his own. The greatest harmony prevailed in this little society; their only quarrels, and these rarely happened, being according to their own expression, guarrels of the mouth: they are honest in their dealings, which consist of bartering different arti- |

cles for mutual accommodation. Their habitations are extremely neat. The little village of Pitcairn forms a pretty square, the houses at the upper end of which are occupied by the patriarch John Adams, and his family, consisting of his old blind wife, and three daughters from fifteen to eighteen years of age, and a boy of eleven; a daughter of his wife by a former husband, and a son in law. "On the opposite side is the dwelling of Thursday October Christian; and in the centre is a smooth verdant lawn, on which the poultry are let loose, fenced in so as to prevent the intrusion of the domestic quadrupeds. All that was done, was obviously undertaken on a settled plan, unlike to any thing to be met with on the other Islands. In their houses too they had a good deal of decent furniture, consisting of beds laid upon bedsteads with neat coverings; they had also tables and large chests to contain their valuables and clothing, which is made from the bark of a certain tree, prepared chiefly by the elder Otaheitan females. Adams's house consisted of two rooms, and the windows had shutters to pull to at night. The younger part of the sex are as before stated, employed with their brothers under the direction of their common father Adams, in the culture of the ground, which produced cocoa nuts, bananas, the bread fruit tree, yams, sweet potatoes and turnips. They have also plenty of hogs and goats; the woods abound with a species of wild hog, and the coasts of the Island with several kinds of good fish. "Their agricultural implements are made by themselves from the iron supplied by the Bounty, which with great labour they beat out into spades, hatchets, crows, &c. This was not all, the good old man kept a regular journal, in which was entered the nature and quantity of work performed by each family, what each had received, and what was due on account. There was it seems besides private property, a sort of general stock out of which articles were issued on account, to the several members of the community; and for mutual accommodation exchanges of one kind of provisions for another were very frequent, as salt for fresh provisions, vegetables and fruit for poultry, fish, &c. also when the stores of one family were low or wholly expended, a fresh supply was raised from another, or out of the general stock, to be repaid when circumstances were more favourable; all of which was carefully noted down in John Adams's Journal. |

"But what was most gratifying of all to the visitors, was the simple, and unaffected manner in which they returned thanks to the Almighty for the many blessings they enjoyed. They never failed to say grace before and after meals, to pray every morning at sun-rise, and they frequently repeated the Lord's prayer and the creed. 'It was truly pleasing,' says Captain Pipon, 'to see these poor people so well disposed to listen so attentively to moral instruction, to believe in the attributes of God, and to place their reliance on divine goodness.' The day on which the two captains landed was Saturday the 17th September; but by John Adams's account it was Sunday the 18th, and they were keeping the Sabbath by making it a day of rest and prayer. "This was occasioned by the Bounty having proceeded thither by the eastern route, and our frigates having gone to the westward; and the Topaz found them right according to his own reckoning, she having also approached the island from the eastward. Every ship from Europe proceeding to Pitcairn's Island round the cape of Good Hope will find them a day later, – as those who approach them round Cape Horn, a day in advance, as was the case with Captain Folger, and the Captains Sir T. Staines and Pipon. The visit of the Topaz is of course, as a notable circumstance, marked down in John Adams's Journal. The first ship that appeared off the island was on the 27th December, 1795; but as she did not approach the land, they could not make out to what nation she belonged. A second appeared some time after, but did not attempt to communicate with them. A third came sufficiently near to see the natives and their habitations, but did not attempt to send a boat on shore; which is the less surprising, considering the uniform ruggedness of the coast, the total want of shelter, and the almost constant and violent breaking of the sea against the cliffs. The good old man was anxious to know what was going on in the world, and they had the means of gratifying his curiosity by supplying him with some magazines and modern publications. His library consisted of the books that belonged to Admiral Bligh, but the visitors had not time to inspect them. "They inquired particularly after Fletcher Christian. This ill-fated young man, it seems, was never happy after the rash and inconsiderate step which he had taken; he became sullen and morose, and practised the very same kind of conduct towards his companions |

in guilt, which he and they so loudly complained against, in their late commander. Disappointed in his expedition to Otaheite, and the Friendly Islands, and most probably dreading a discovery, this deluded youth committed himself and his remaining confederates to the mere chance of being cast upon some desert island, and chance threw them on that of Pitcairn's. Finding no anchorage near it, he ran the ship upon the rocks, cleared her of the live stock and other articles, which they had been supplied with at Otaheite, when he set her on fire, that no trace of inhabitants might be visible, and all hopes of escape cut off from himself and his wretched followers. He soon however disgusted both his own countrymen and the Otaheitans, by his oppression and tyrannical conduct; they divided into parties, and disputes, affrays, and murders, were the consequence. His Otaheitan wife died within a twelvemonth from their landing, after which he carried off one that belonged to an Otaheitan man, who watched for an opportunity of taking his revenge, and shot him dead while digging in his own field. Thus terminated the miserable existence of this deluded young man, who was neither deficient in talent nor energy, nor in connexions, and who might have risen in the service, and become an ornament to his profession. "John Adams declared, as it was natural enough he should do, his abhorrence of the crime in which he was implicated, and said he was sick at the time in his hammock. This we understand is not true, though he was not particularly active in the mutiny; he expressed the utmost willingness to surrender himself and be taken to England; indeed he rather seemed to have an inclination to revisit his native country, but the young men and women flocked round him, and with tears and intreaties begged that their father and protector might not be taken from them, for without him they must all perish. It would have been an act of the greatest inhumanity to remove him from the island; and it is hardly necessary to add, that Sir Thomas Staines lent a willing ear to their intreaties, thinking no doubt, as we feel strongly disposed to think, that if he were even among the most guilty, his care and success in instilling religious and moral principles into the minds of this young and interesting society, have in a great degree redeemed his former crimes. This island is about six miles long by three broad, covered with wood, and the soil of course very rich: situated under the |

parallel of 25° south latitude, and in the midst of such a wide expanse of ocean, the climate must be fine and admirably adapted for the reception of all the vegetable productions of every part of the habitable globe. Small therefore as Pitcairn's Island may appear, there can be little doubt that it is capable of supporting many inhabitants; and the present stock being of so good a description, we trust they will not be neglected. "In the course of time the patriarch must go hence; and we think it would be exceedingly desirable that the British nation would provide for such an event, by sending out, not an ignorant and idle evangelical missionary; but some zealous and intelligent instructor, together with a few persons capable of teaching the useful trades or professions. "On Pitcairn's Island there are better materials to work upon than missionaries have yet been so fortunate as to meet with, and the best results may reasonably be expected. "Something we are bound to do for these blameless and interesting people. The articles recommended by Captain Pipon appear to be highly proper; cooking utensils, implements of agriculture, maize, or the Indian corn, the orange tree from Valparaiso, a most grateful fruit in a warm climate, and not known in the Pacific Islands, and that root of plenty (not of poverty as a wretched scribbler has called it) the potatoe, bibles, prayer books, and a proper selection of other books, with paper, and other implements of writing. The visitors supplied them with some tools, kettles, and other articles, such as the high surf would permit them to land, but to no great extent; many things are still wanting for their ease and comfort. The descendants of these people by keeping up the Otaheitan language, which the present race speak fluently, might be the means of civilizing the multitudes of fine people scattered over the innumerable islands of the great Pacific. "We have only to add, that Pitcairn's Island seems to be so fortified by nature as to oppose an invincible barrier to an invading enemy; there is no spot apparently where a boat can land with safety, and perhaps not more than one where it can land at all; an everlasting swell of the ocean rolls in on every side, and breaks into foam against its rocky and iron bound shores." To this information may be added the following extracts from the 5th number of the Quarterly Review, (Febuary 1810,) pages 23 |

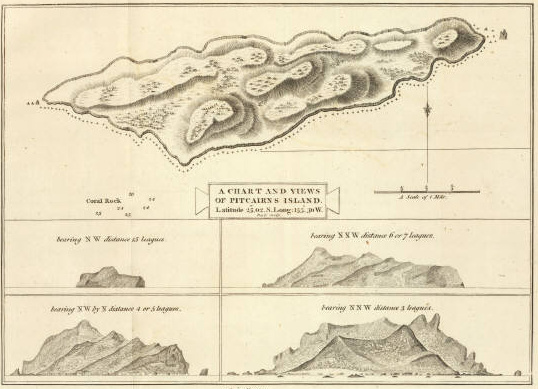

carterets views of pitcairn's island.

carterets views of pitcairn's island.

|

and 24. "About four years after their arrival (on Pitcairn's Island,) a great jealousy existing, the Otaheitans secretly revolted and killed every Englishman except himself (Smith,) whom they severely wounded in the neck with a pistol ball. The same night the widows of the deceased Englishmen arose and put to death the whole of the Otaheitans, leaving Smith the only man alive upon the island, with eight or nine women, and several small children. "The second mate of the Topaz asserts that Christian, the ring-leader, became insane shortly after their arrival on the island, and threw himself off the rocks into the sea. Another died of a fever before the massacre of the remaining five took place." Some remarks will hereafter be made upon the difference between this account of the mode of Christian's death, and that already quoted from the Quarterly Review, under the date of July 1815. As the particulars of the history of Pitcairn's Island, are of general interest, I shall here insert an extract from Carteret's Voyage, at page 561, in the 1st volume of Dr. Hawkesworth's collection. "1767. We continued our course westward till the evening of Thursday the 2d of July, when we discovered land to the northward of us. Upon approaching it the next day, it appeared like a great rock rising out of the sea. It was not more than five miles in circumference, [now said to be six miles long, and three broad,] and seemed to be uninhabited. It was however covered with trees, and we saw a small stream of fresh water running down one side of it. I would have landed upon it, but the surf, which at this season broke upon it with great violence, rendered it impossible. I got soundings on the west side of it, at somewhat less than a mile from shore, in twenty five fathoms, with a bottom of coral and sand, and it is probable that in fine summer weather, landing here may not only be practicible, but easy. We saw a great number of sea birds hovering about it, at somewhat less than a mile from the shore, and the sea here seemed to have fish. It lies in latitude 25°, 2' south, longitude 133°, 21' west, and about a thousand leagues to the westward of the continent of America. It is so high that we saw it at the distance of more than fifteen leagues; and it having been discovered by a young gentleman, son to Major Pitcairn of the marines, who was unfortunately lost in the Aurora, we called it PITCAIRN'S ISLAND." |

This description of it, and the fact that it was so high as to be seen at the distance of fifteen leagues, have led some to believe that it is not the same with the Encarnacion of Quiros, as is supposed in the Quarterly Review. Dalrymple's Collection, Quiros's Voyage, page 107, has been cited by a writer to show that the Encarnacion "was small, about four leagues in circuit, all flat and level with the water, with few trees, and for the greater part sand." One other article, concerning the geography of the island and the sympathies of the inhabitants, ought to be selected. In the notes of a poem, Christina the Maid of the South Seas, written by Mary Russell Mitford, at page 304 is the following testimony, pointed out to me by a friend. "I have the authority of the gentleman, who favoured me with most of the particulars relative to Pitcairn's Island, for stating that there is a cavern under a hill, to which Smith, the Fitzallan of my poem, had once retired at the approach of some English vessel, as a place of concealment and security. The ships passed on, but the cave was still held sacred by the islanders as a means of future protection for their revered benefactor. Never may that protection be required! Never may an English vessel bring other tidings than those of peace and pardon to one who has so fully expiated his only crime! Sufficient blood has been already shed to satisfy the demands of justice; and mercy may now raise her voice at the foot of that throne where she never pleads in vain. On being asked by Captain Folger, if he wished his existence to remain a secret, Smith immediately answered, "No," and pointing to the young and blooming band by whom he was surrounded, continued, "Do you think any man could seek my life with such a picture as this before his eyes?" This sentiment of forgiveness, and the deprecation of all future prosecution on the part of the British government, will I think meet the feelings of every benevolent heart. I have now given to my readers all the documents which have been already printed, so far as I have read them, and as they are necessary to furnish an account of the origin, progress, and present state of the interesting inhabitants of Pitcairn's Island. Before I record the further information, which I obtained from Captain Folger in conversation, I shall introduce an extract from a let- |

ter of his to me, bearing a very recent date, and written in the state of Ohio, where he now resides. Although most of the facts contained in it have been related already, yet there are some new circumstances mentioned which make it worthy of a place in this volume. "Kendal, June 2d,1816.

Respected Friend, Your favour of the 12th ultimo, I received last mail from the eastward, and as it returns tomorrow, I take the opportunity of forwarding you an answer. The Bounty it seems sailed from England in 1787, and after the mutiny took place, the particulars of which are so well known, the mutineers returned with her to Otaheite. After many delays on that coast, a part of the crew under the command of Christian went in search of a group of islands, which you may remember to have seen on the chart, placed under the head of Spanish discoveries. They crossed the situation of those imaginary isles, and satisfied themselves that no such existed. They then steered for Pitcairn's Isle, discovered by Capt. Carteret, and by him laid down in latitude 25° 2' south, and longitude by account from Massafuero, 133° 21' west, where they arrived and took every thing useful out of the ship, ran her on shore, and broke her up. In February, 1808, on my passage across the Pacific ocean, I touched at Pitcairn's Island, thinking it was uninhabited; but to my astonishment I found Alexander Smith, the only remaining Englishman who came to that place in the Bounty, his companions having been massacred some years before. He had with him thirty-four women and children. The youngest did not appear to be more than one week old. I stayed with him five or six hours, gave him an account of some things that had happened in the world since he left it, particularly their great naval victories, at which he seemed very much elated, and cried out, "Old England forever!" – In turn he gave me an account of the mutiny and the death of his companions, a circumstantial detail of which could I suppose be of little service to you in the work in which you are at present engaged. The latitude is 25° 2' south, and the longitude, by mean of nine sets of observations, 130° west. Capt. Carteret might well have erred three or four |

degrees in his longitude, in an old crazy ship with nothing but his log to depend on. I should be pleased to see your work when it is finished. I think it must be interesting. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * I remain, with esteem,

Your assured friend, MAYHEW FOLGER.

With this gentleman I became acquainted in the year 1800, at the island of Massafuero. We were then on voyages for seals, and had an opportunity to be together for many months. His company was particularly agreeable to me, and we were often relating to each other our adventures. Among other topics of conversation, the fate of the Bounty was several times introduced. I showed to him the copy of the Journal of Edwards, which I had taken at Timor, and we were both much interested to know what ultimately became of Christian, his ship, and his party. It is not easy for landsmen, who have never had personal experience of the sufferings of sailors at sea, and on savage coasts or desolate islands, to enter into their feelings with any thing like an adequate sympathy. We had both suffered many varieties of hardship and privation, end our feelings were perfectly alive to the anxieties and distresses of a mind under the circumstances of Christian, going from all he had known and loved, and seeking as his last refuge a spot unknown and uninhabited, The spirit of crime is only temporary in the human soul, but the spirit of sympathy is eternal. Repentance and virtue succeed to passion and misconduct, and while the public may continue to censure and frown, our hearts in secret plead for the returning and unhappy transgressor. It was with such a state of mind that Folger and myself used to speak of the prospects before the mutineers of the Bounty, when she was last seen steering to the northwest from Otaheite on the open ocean, not to seek friends and home, but a solitary region, where no human face, besides the few now associated in exile, should ever meet their eyes. After several years had elapsed, and we had navigated various seas, we fortunately lived to meet each other again in Boston, when it was in his power to renew our old conversation about the Bounty, and to gratify the curiosity and interest which we had so long |

cherished in common. The Topaz in which he sailed was fitted and owned in this place by James and Thomas H. Perkins Esquires, and crossed the south Pacific ocean in search of islands for seals. Being in the region of Pitcairn's Island, according to Carteret's account, he determined to visit it, hoping that it might furnish him with the animals which were the objects of his voyage. As he approached the island, he was surprised to see smokes ascending from it, as Carteret had said it was uninhabited. With increased curiosity he lowered a boat into the water, and embarked in it for the shore. He was very soon met by a double canoe, made in the manner of the Otaheitans, and carrying several young men, who hailed him in English at a distance. They seemed not to be willing to come near to him till they had ascertained who he was. He answered, and told them he was an American from Boston. This they did not immediately understand. With great earnestness they said, "You are an American; you come from America; where is America? Is it in Ireland?" Captain Folger thinking that he should soonest make himself intellegible to them by finding out their origin and country, as they spoke English, inquired, "Who are you?" – "We are Englishmen." – "Where were you born?" – "On that island which you see." – "How then are you Englishmen, if you were born on that island, which the English do not own, and never possessed?" – "We are Englishmen because our father was an Englishman? – "Who is your father?" – With a very interesting simplicity they answered, "Aleck." – "Who is Aleck?" – " Do'n't you know Aleck?" – How should I know Aleck?" – Well then, did you know Captain Bligh of the Bounty?" – At this question, Folger told me that the whole story immediately burst upon his mind, and produced a shock of mingled feelings, surprise, wonder, and pleasure, not to be described. His curiosity which had been already excited so much on this subject, was revived, and he made as many inquiries of them as the situation in which they were, would permit. They informed him that Aleck was the only one of the Bounty's crew who remained alive on the island; they made him acquainted with some of the most important points in their history; and with every sentence increased still more his desire to visit the establishment and learn the whole. Not knowing whether it would be proper and safe to land without giving notice, as the fears of the surviving |

mutineer might be awakened in regard to the object of the visit, he requested the young men to go and tell Aleck, that the master of the ship desired very much to see him, and would supply him with any thing which he had on board. The canoe carried the message, but returned without Aleck, bringing an apology for his not appearing, and an invitation for Captain Folger to come on shore. The invitation was not immediately accepted, but the young men were sent again for Aleck, to desire him to come on board the ship, and to give him assurances of the friendly and honest intentions of the master. They returned however again without Aleck, said that the women were fearful for his safety, and would not allow him to expose himself or them by leaving their beloved island. The young men pledged themselves to Captain Folger that he had nothing to apprehend if he should land, that the islanders wanted extremely to see him, and that they would furnish him with any supplies which their village afforded. After this negotiation Folger determined to go on shore, and as he landed he was met by Aleck and all his family, and was welcomed with every demonstration of joy and good will. They escorted him from the shore to the house of their patriarch, where every luxury they had was set before him, and offered with the most affectionate courtesy. He, whom the youths in the canoe, with such juvenile and characteristic simplicity, had called Aleck, and who was Alexander Smith, now began the narrative, the most important parts of which have already been detailed. It will be sufficient for me to introduce here such particulars only as have not been mentioned, but are well fitted to give additional interest to the general outline, by a few touches upon the minute features. Smith said, and upon this point Captain Folger was very explicit in his inquiry at the time as well as in his account of it to me, that they lived under Christian's government several years after they landed; that during the whole period they enjoyed tolerable harmony; that Christian became sick and died a natural death; and that it was after this when the Otaheitan men joined in a conspiracy and killed the English husbands of the Otaheitan women, and were by the widows killed in turn on the following night. Smith was thus the only man left upon the island. The account by Lieut. Fitzmaurice, as he professed to receive it from the second mate of the |

Topaz, is, that Christian became insane, and threw himself from the rocks into the sea. The Quarterly Reviewers say that he was shot dead while digging in the field, by an Otaheitan man, whose wife he seized for his own use. Neither of these accounts is true, as we are at liberty to affirm from the authority of Captain Folger, whose information must be much more direct and worthy of confidence than that of the second mate, of Fitzmaurice, or of the re-viewers. The last are evidently desirous of throwing as much shade as possible upon the character of Christian. Smith had taken great pains to educate the inhabitants of the island in the faith and principles of chriatianity. They were in the uniform habit of morning and evening prayer, and were regularly assembled on Sunday for religous instruction and worship. It has been already mentioned that the books of the Bounty furnished them with the means of considerable learning. Prayer books and bibles were among them, which were used in their devotions. It is probable also that Smith composed prayers and discourses particularly adapted to their circumstances. He had improved himself very much by reading, and by the efforts he was obliged to make to instruct those under his care. He wrote and conversed extremely well, of which he gave many proofs in his records and in his narrative. The girls and boys were made to read and write before Captain Folger, to show him the degree of their improvement. They did themselves great credit in both, particularly the girls. The stationary of the Bounty was an important addition to the books, and was so abundant that the islanders were not yet in want of any thing in this department for the progress of their school. The journal of Smith was so handsomely kept as to attract particular attention, and excite great regret that there was not time to copy it. The books upon the island must have created and preserved among the inhabitants an interest in the characters and concerns of the rest of mankind. This idea will explain much of their intercourse with Captain Folger, and the difference between them and the other South Sea islanders in this respect. When Smith was asked if he had ever heard of any of the great battles between the English and French fleets in the late wars, he answered, "How could I, unless the birds of the air had been the heralds? – He was told of the victories of Lord Howe, Earl St. Vincent, Lord Duncan, and Lord Nelson. He listened with atten- |

tion till the narrative was finished, and then rose from his seat, took off his hat, swung it three times round his head with three cheers, threw it on the ground sailor like, and cried out "Old- England forever!" – The young people around him appeared to be almost as much exhilarated as himself, and must have looked on with no small surprize, having never seen their patriarchal chief so excited before. Smith was asked, if he should like to see his native country again, and particularly London, his native town. He answered, that he should, if he could return soon to his island, and his colony; but he had not the least desire to leave his present situation forever. – Patriotism had evidently preserved its power over his mind, but a stronger influence was generated by his new circumstances, and was able to modify its operations. The houses of this village were uncommonly neat. They were built after the manner of those at Otaheite. Small trees are felled and cut into suitable lengths; they are driven into the earth, and are interwoven with bamboo; they are thatched with the leaves of the plantain and cocoa-nut; and they have mats on the ground. – My impression is, that Folger told me some of them were built of stone. The young men laboured in the fields and the gardens, and were employed in the several kinds of manufactures required by their situation. They made canoes, household furniture of a simple kind, implements of agriculture, and the apparatus for catching fish. – The girls made cloth from the cloth tree, and attended to their domestic concerns. They had several amusements, dancing, jumping, hopping, running, and various feats of activity. They were as cheerful as industrious, and as healthy and beautiful as they were temperate and simple. Having no ploughs and no cattle, they were obliged to cultivate their land by the spade, the hoe, and other instruments for manual labour. The provision set before Captain Folger consisted of fowls, pork, and vegetables, cooked with great neatness and uncommonly well. The fruits also were excellent. The apron and shawl worn by the girls were made of the bark of the cloth tree. This is taken off the trunk, not longitudinally, but round, like the bark of the birch. It is beaten till it is thin and soft, |

and fit for use. The natural colour is buff, but it is dyed variously, red, blue, and black, and is covered with the figures of animals, birds, and fish. The inquiry was made of Smith very particularly in regard to the conduct of the sexes toward each other, and the answer was given in such a manner as entirely to satisfy Captain Folger that the purest morals had thus far prevailed among them. Whatever might be the liberties allowed by the few original Otaheitan women remaining, the young people were remarkably obedient to the laws of continence, which had been taught them by their common instructor and guide. Smith is said, by later visitors, to have changed his name, and taken that of John Adams. This probably arose from a political conversation between him and Captain Folger, and from the account then given him of the Pandora under the command of Captain Edwards, who was sent out in pursuit of the Bounty and the mutineers. The fears of Smith were somewhat excited by this last article of intelligence. As the federal constitution of the United States of America had gone into operation since the mutiny; as Captain Folger had given Smith an animating and patriotic account of the administration of the new government and its effects upon the prosperity of the country; and as the name of President Adams had been mentioned, not only with respect as an able statesman and a faithful advocate of civil liberty, but as an inhabitant of the commonwealth in particular where Folger lived; it is thought to be probable enough that this is the circumstance which suggested the name that Smith afterward adopted. When he was about to leave the island, the people pressed round him with the warmest affection and courtesy. The chronometer which was given him, although made of gold, was so black with smoke and dust that the metal could not be discovered. The girls brought some presents of cloth, which they had made with their own hands, and which they had dyed with beautiful colours. Their unaffected and amiable manners, and their earnest prayers for his welfare, made a deep impression upon his mind, and are still cherished in his memory. He wished to decline taking all that was brought him in the overflow of friendship, but Smith told him it would hurt the feelings of the donors, and the gifts could well be spared from the island. He made as suitable a return of |

presents as his ship afforded, and left this most interesting community with the keenest sensations of regret. It reminded him of Paradise, as he said, more than any effort of poetry or the imagination. The conversations between me and Captain Folger upon this subject, were all previous to the dates of the several printed accounts, to which I have referred in this chapter. There are a few points only in which the article in the Quarterly Review differs from the impressions upon my mind at the time when I read it. In the volume for 1810, as well as in that for 1815, the Reviewers appear to have gone out of their way, and to have taken very unworthy pains to connect slanders against my countrymen with their remarks upon Pitcairn's Island. Perhaps in the next chapter, which is to contain some reflections upon the whole subject, this topic may be taken up. . In regard to the extent of the population of the island a remark may be made. Captain Folger says there were thirty four in eighteen hundred and eight. Sir Thomas Staines mentions forty in eighteen hundred and fourteen. The Review afterwards says, there were about forty six besides a number of infants. As every one of the forty whom Sir Thomas Staines saw, spoke good English, and as this cannot be applied to the very young children, there must have been a larger number on the island at that time. The population now must be, at the lowest estimate, not less than sixty. |

CHAPTER VI.

The mutiny, which happened in the Bounty, invites some reflections. This subject was often discussed between Commodore McClure, his officers, and the Dutch gentlemen at Timor, who saw Lieutenant Bligh and his companions on their arrival at that island, and who were acquainted both with him and with them during their stay there. The manner in which his officers spoke of him, and the kind of treatment which they observed in regard to him, are still distinctly remembered as stated at Timor. The mutineers are not so much excluded from sympathy among the gentlemen at that place, as they possibly may be among those in England who have only read the story of one of the parties. My mind was prevented from falling into rash conclusions and censures, by the conversations in which I then joined; and it has been placed in a still more impartial state by the information which Captain Folger gave me as he received it from Smith. Extreme depravity rarely belongs to persons educated as Christian and his adherents were, and who have manifested so many virtues on other occasions. Acts of a desperate character are not likely to have been performed by such men without considerable provocation. Lieutenant Bligh, I suppose, is still living, and it seems that he has become an admiral. It is proper to speak of him with respect, although we may ascribe to him the ordinary failings of our nature. Anecdotes have been told to me concerning his conduct at Copenhagen with Lord Nelson, which naturally prevent me from viewing him as beyond those weaknesses and defects which most of us are so often obliged to acknowledge, and by which our pride receives a salutary mitigation. The Quarterly Reviewers are unwise, if they wish to be considered as the friends of Admiral Bligh, to provoke an examination of this subject by |